PARVOVIRUS

What is Canine Parvovirus (CPV)?

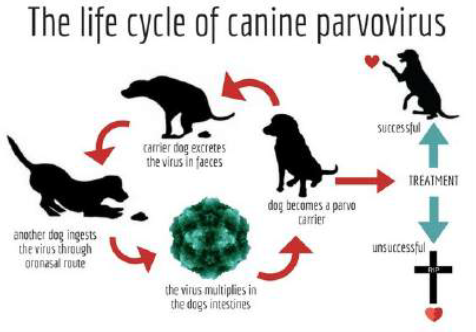

CPV appeared as a canine pathogen in 1978 and is thought to have come about as a mutation of the feline panleukopaenia virus. CPV is transmitted by a faeco-oral route. In other words, it is a viral infection that is spread by contact with infected dogs or contact with their faeces, hair, sniffing, feet of infected dogs, eating infected faeces, shared bedding, feeding and water bowl, including contamination from shoes, pavements, or any area where an infected dog has visited. This means that direct contact between dogs is not needed to spread the virus. CPV in the environment is resistant to heat, some detergents and alcohol and can live in the soil for several months. CPV affects dogs aged between 6 weeks to 6 months, as most adult dogs are immune due to vaccinations or previous infections. That is not to say that an adult dog will not get the virus. The virus attacks the rapidly dividing cells in the body, like the lining of the digestive tract or in developing white blood cells. Dogs infected with the virus show clinical signs usually within 7-10 days of the initial infection. PVC results in the puppy having bloody diarrhoea, vomiting and a compromised immune function.

What signs should you look for?

Loss of appetite, vomiting, severe diarrhoea; often bloody, abdominal pain and bloating, acting tired and weak. Fever can occur, but most have a low temperature and severe dehydration. A good indication of CPV is when the dog presents with bloody stained faeces that has a yellowish tinge and a very distinct and unpleasant smell.

Prevention

Be informed and proactive. Recovered dogs can shed parvovirus for up to two weeks after illness. Therefore, it is advisable to keep dogs away from dogs who have recently had the disease. The best method is to vaccinate your puppy. It is a recommended core vaccine for all dogs. These include the DHPP vaccine (Distemper, Hepatitis, Parainfluenza and Parvovirus). Puppies receive a CPV vaccination as part of the vaccines given at 6 – 8 weeks, repeated at 3 – 4 weeks until puppies are 16 weeks of age. Booster at one year of age and then every 3 years thereafter are advised to maintain immunity thought-out adulthood. When puppies have had the vaccination, it is advisable to keep them indoors for up to 7 days, as they will be shedding the virus. Proper hygiene is also important. Try to avoid letting your puppy or adult dog encounter the faecal waste of other dogs while walking or playing outdoors. Picking up and disposing of your dog’s waste material is one way of limiting the spread of the disease.

Socializing your pup

The socialization dilemma – you now know that your puppy is not fully protected until he has had his 16-week vaccine, which overlaps with the critical socialization period of a puppy (between 3 – 16 weeks). How do you get him socialized without putting him at unnecessary risk of contracting the virus? You do so with caution and common sense. As discussed above, there is no way you can 100% protect your puppy from the virus (you could bring it into your house on your feet). However, the risk of parvo with ‘CAREFUL’ socialization is much lower than the risk of serious behaviour problems with ‘NO’ socialization.

In general, puppies can start classes as early as 8 weeks of age. They should have received a minimum of one set of vaccines at least 7 days before the first class and vaccines should be kept up throughout the class. The American Veterinary Society of Animal Behaviour believes that it should be the standard of care for puppies to receive such socialization before they are fully vaccinated. Socialization is particularly important and should occur as part of a well-organized program that incorporates other preventive measures. These include proper vaccination protocols, cleaning up of faeces and disinfecting the area if there is a suspected contamination. We at the club, ensure that these protocols are adhered to, to protect all member’s dogs. Try to avoid dog parks, beaches, walking down the street or heavily attended areas until after the 16 weeks.

Can it be treated successfully?

There is no treatment to kill this virus once it infects a dog, but the virus does not actually cause death. Death occurs due to secondary infections and dehydration. Therefore, it is important to get your pup to the vet as soon as possible if he is displaying any of the symptoms as described above. However, survival up to seven days after clinical signs is associated with recovery and lifelong immunity. Survival of at least 90% of cases are known where prompt, aggressive therapy is implemented.

Can you kill the virus in the environment?

Due to the stability of the CPV, it is therefore, important properly to disinfect contaminated areas. You can do this by cleaning food, and water bowls and any other infected areas with 250L of chlorine bleach in five litres of water. It is imperative that chlorine bleach or glutaraldehyde-based disinfectants be used as there are many products out there that will not kill the CPV.

Why do vaccines fail?

Vaccination may fail from variable protection given by Maternally Derived Antibodies (MDA). The window period exists in puppies from 6 weeks where declining MDA can allow natural infection, but also prevent an effective vaccine-induced humeral response. Modern high-titer vaccines are designed to overcome MDA and try to give immunity before MDA wears off. Rottweilers, Dobermans (black and tan breeds) and Staffordshire Bull Terriers are at a higher risk of infection due to suspected poor humeral responses to vaccination and increased MDA resistance.

http://www.arizonapetvet.com/blog/canine-parvoviruslearning-how-to-prevent-is-the-key/

Can it be transmissible to Humans?

There is no evidence that CPV is transmissible to cats or humans. However, people can spread it to other dogs if they have the virus on their hands or clothing and then touch another dog or their environment (e.g., kennel, toys, grooming tools).

References:

1. Spencer S, Tappin. S. Available from www.vettimes.co.uk: Recommendations for treating and preventing canine parvovirus | Vet Times

2. https://avsab.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Puppy_Socialization_Position_Statement_Download_-_10-3-14.pdf

3. Otto C M, Jackson C B, Rogell E J et al (2001). Recombinant bactericidal/ permeability-increasing protein (rBPI21) for treatment of parvovirus enteritis: a randomised, double-blinded, placebo controlled trial, J Vet Intern Med15(4): 355–360

4. Parvo Fact Sheet (grc.qld.gov.au)

5. https://www.aaha.org/aaha-guidelines/vaccination-canine-configuration/vaccinationcanine/

6. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jsap.2_12431